How Uber turned phone lists into a multi-billion dollar driver network

Discover how Uber built its early driver network with cold calls, manual onboarding, and word-of-mouth referrals before product-market fit, funding, or scale. A tactical guide for marketplaces on building supply from scratch.

What you'll learn

More about the expert

Scott joined in the pre-UberX days, when the platform only supported black cars and growth depended on raw hustle, not algorithmic targeting.

This playbook breaks down how Scott and his team manually seeded supply with cold calls, built trust in-person, and used driver referrals to spark a growth loop that scaled fast.

The old-school tactic that kickstarted supply

Before performance marketing and mobile-first onboarding flows, Uber got on the phone.

Literally.

Launching in Atlanta, as well as the 10 other cities they serviced back in 2012, meant manually compiling a list of local limo companies through Yelp, Google, or boots-on-the-ground visits. They’d scrape contact info, identify decision-makers, and cold call every single one. Why?

Because it worked.

Also because apps weren’t bloated with ten layers of CRM logic and AI scoring back then. You just picked up the phone and called.

The anti-pitch

Service-based marketplaces, like the one Uber lived in, was highly phone-based back then. Taxi companies and limo operators picked up the phone since calls could mean a new client. Uber didn’t lead with features or a brand name. The opening line wasn’t “Join Uber.” It was:

Simple. Relatable. Outcome-focused.

With no upfront cost and guaranteed hourly pay, limo companies were incentivized to try Uber risk-free. It was a win-win. Uber filled supply, and companies monetized idle cars.

But this wasn’t a one-size-fits-all script.

Scott's team had to adjust their messaging based on market sentiment. Sometimes leading with the Uber name, sometimes holding it back to avoid regulatory scrutiny.

Marketplace founders take note: Simplicity wins. Founders today often obsess over pitch decks and funnel optimization, but forget the power of a direct phone call paired with the right hook.

A taxi turf war was brewing with Uber at the helm

In many cities, Uber was operating in a legal gray area, drawing heat from taxi commissions and local regulators who saw it as a threat to entrenched systems. Word would spread fast, sometimes before Uber even launched, poisoning the well with misinformation or resistance. So in more sensitive markets, Uber's ops teams played it cautiously, pitching the opportunity first, and only name-dropping Uber once trust had been built.

Uber's early tactic snapshot:

- Build a list of credible operators: Yelp, Google, spreadsheets. Manual but effective.

- Call and pitch: Emphasize extra income, not brand names.

- Incentivize trial: Hourly guarantees to minimize perceived risk.

- Reduce friction: Uber often created driver accounts themselves.

- Stay close to the ground: Drivers would visit the office, or even Scott’s apartment.

Cold calling wasn’t scalable long-term, but it was the fastest way to bootstrap a new city. It worked because it was direct, personal, and tailored but only up to a point. Scott noted that while cold calling was essential to getting early cars on the road, it quickly hit its ceiling. You could only call so many limo companies. And once those networks were tapped, the strategy couldn’t support 10x or 100x growth on its own.

Plus, not every market responded the same way.

Some markets had caps or regulatory heat that made cold calls a gamble. So from the start, Uber knew it needed a second engine to keep growth alive.

The referral loop that fueled the fire

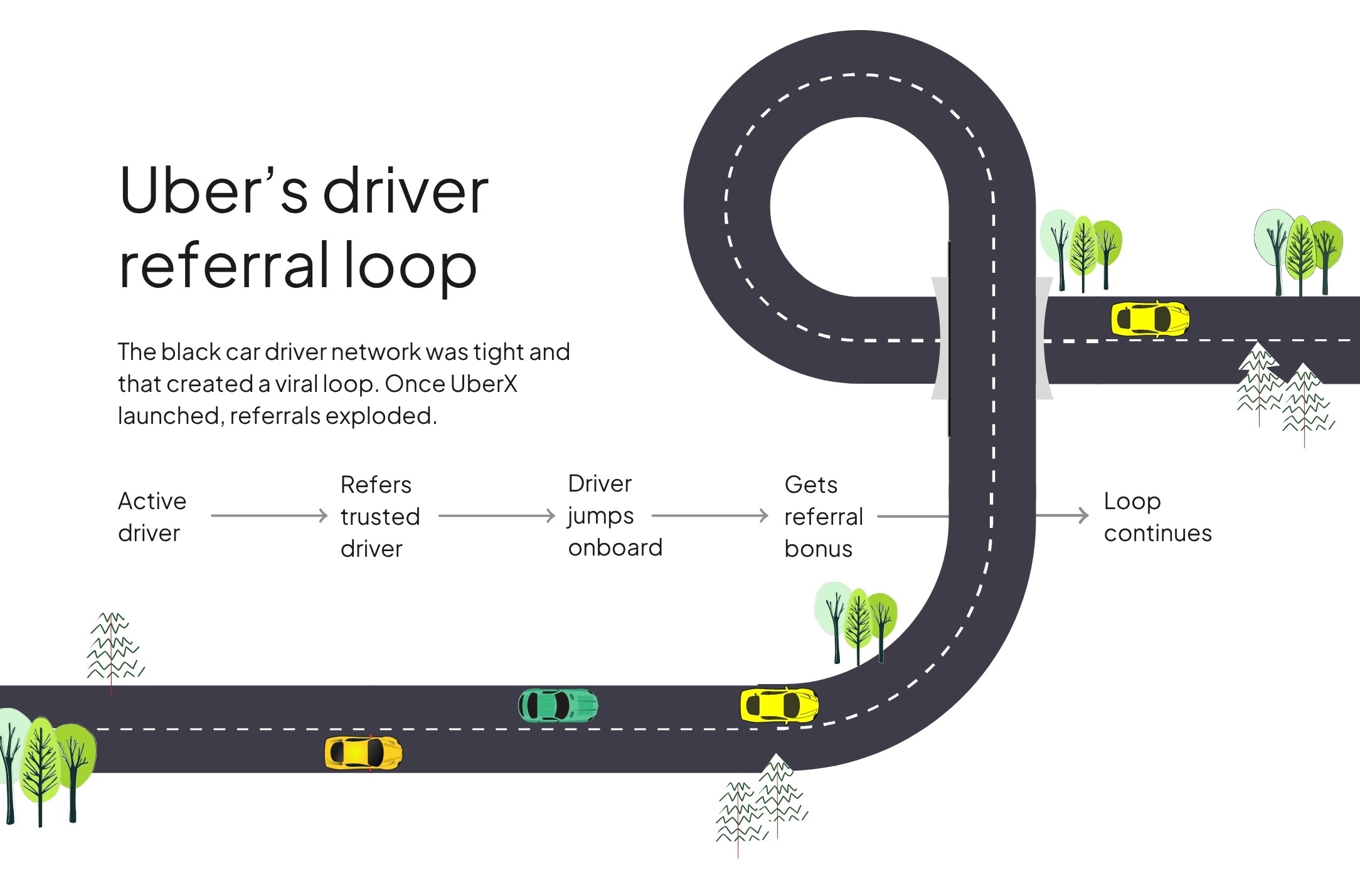

Once a few drivers were active, Uber tapped into an organic driver behavior: word-of-mouth.

Texts and face-to-face communication worked better as most drivers didn’t check email regularly, and many didn’t even have one. Texting was direct, timely, and far more effective at driving action. Meeting in person at the office, during onboarding, or even at the airport lot built trust fast.

One thing to know about drivers? They knew other drivers…

who knew other drivers…and so on.

And if they were earning with Uber, they were happy to tell their friends. Uber leaned into this by:

- Offering referral bonuses

- Texting drivers directly about referral programs

- Promoting offers in person, at the office, onboarding, or airport lots

Referrals became a core acquisition engine because they brought in high-quality supply. Power drivers didn’t just know the job, they knew other drivers who could crush it too. And when those friends showed up at the office with a clean car and a nod from someone already earning, conversion was basically a lock.

Cost per onboarded driver? In Atlanta, Scott paid just $25 per referral at the start. Drivers would walk into the office with their friends, and Scott would onboard them on the spot. No funnel drop-off, no ghosting. Just fast, warm leads who hit the road.

Retention also told a story. Drivers who referred others especially full-time, pro drivers with years of experience, tended to stick around longer than part-time UberX drivers who only logged a few hours per week.

Even before UberX, the black car driver network was tight and that created a viral loop. Once UberX launched, referrals exploded. Suddenly, anyone with a qualifying car could sign up. And the payout structure grew fast.

Aggressively fast.

Reaching $200, $500 and, specifically in San Francisco, even got up to a lofty $1,000 per referral.

Tactic snapshot: From cold call to community playbook

- Manual tracking: Notes in CRM or spreadsheets before automation

- Word-of-mouth over email: Face-to-face communication worked better for Uber's market

- White-glove onboarding: Uber staff handled everything to remove friction

- Incentives scaled with competition: Cities in battle zones (NYC, SF) got the highest bonuses

What made the loop work?

Drivers were evangelists, not just users.

They believed in the product, trusted the team, and made real money. What started as a turf war quietly turned into a movement and rewrote the rules of urban transportation.

While Scott didn’t share exact revenue figures, given the time, variability across cities, and driver behavior, he made one thing clear: every new car on the road generated more rides, and more rides drove more revenue. Supply was that tightly linked to growth.

“If we added a car, it’d fill up.”

That kind of instant utility made cold calling one of the fastest ways to grow meaningful revenue in a new city, even if it was hard to quantify in dashboards at the time.

Growth means just showing up

Uber’s early ops teams were street-level hustlers. Here are some key steps that they did to make sign-ups and onboarding as easy as possible.

They went where drivers were:

- Airport limo waiting lots

- Outside popular bars

- Local trade shows

- Even drivers’ homes and other hotspots

They brought donuts, coffee, and face time. That built trust; which built Uber’s brand from the ground up.

They removed all friction:

Most limo drivers weren’t about to wrestle with an online form or upload documents from a laptop they didn’t have. So Uber staff handled the entire process from account creation, paperwork, up to verification.

- Signed drivers up themselves

- Gave them stripped-down iPhones with only Uber and all its functions

- OCR-scanned their documents to save time

To speed things up, Uber’s engineering team built a tool that let staff take photos of documents (i.e. licenses and insurance) and automatically extract the necessary info using optical character recognition (OCR) technology. What used to take 30 minutes could now be done in five.

It wasn’t pretty or polished. But it worked and what started as 0 out of 10 cars filled turned into 500 out of 500, and still not enough.

Fun fact: They scaled so fast that they became the largest buyer of iPhones globally at one point.

They worked relentless hours:

Scott built the system and powered it. He consistenly put in 100-hour weeks and handled driver onboarding sessions one-on-one, each lasting 30 to 45 minutes. There was no automation and barely any easy alternative. He created accounts, uploaded documents, answered every question, and got drivers on the road. The infrastructure couldn’t scale yet, but his team made sure the city did. He wasn’t just part of the growth engine. He was the engine.

Founder’s take

“Cold calling isn’t dead. It’s just uncomfortable. Most modern marketers won’t pick up the phone. That’s a competitive advantage if you will.”

- Jonathan Martinez, GrowthPair Co-Founder

There’s a reason this playbook still hits in 2025. At GrowthPair, we’ve helped dozens of startups and almost every breakout moment starts with something most people avoid: direct action.

The reason cold calling worked for Uber is the same reason it works today: speed, signal, and intimacy.

- Speed: You get feedback in real-time. No waiting on click-through rates or landing page tests. A yes or no on the call tells you more than a hundred ad impressions ever could.

- Signal: Hearing someone’s objections sharpens your pitch. And if your offer isn’t landing live, it’s definitely not going to convert on autopilot.

- Intimacy: When you talk to a person, not a persona, you learn how they think, what they fear, and how to actually serve them. That’s product-market insight gold.

Founders today often over-engineer early growth. We obsess over CRMs, onboarding flows, and attribution dashboards. But if you haven’t earned your first 100 users through pure hustle, you’re building on shaky ground.

Tactics that founders can steal today:

- Pick up the phone. You don’t need a CRM to start. Just Google.

- Simplify your pitch. Lead with outcomes, not product.

- Meet the users where they are. Digital is great but so is showing up in person.

- Make onboarding frictionless. High touch > high tech at zero to one.

- Use referrals intentionally. Not for growth hacking, but for trust-building.

- Know your story cold. In a world where everyone has an AI agent with a 200 IQ, there’s going to be a flood of content slop. The only way to stand out is with clarity, conviction, and a sharp value prop that actually resonates.

As Scott put it—

%203.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%202%20(1)%20(1).avif)

.avif)

%201%20(1).avif)

%201.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)

.avif)